Recent Blog Posts

-

06/21/2024VIDEO: What to Expect When You Submit Your Fiber to NEAFP

-

05/24/2024VIDEO: Getting Started Submitting Alpaca Fiber

-

05/24/2024NEW Downloadable Content: Memorial Day Coloring Page

-

05/03/2024Do I need to skirt my fiber before submitting to the fiber pool? NEAFP TV S01 E01

-

03/22/2024Introducing our newest U.S. Alpaca product: Textured Rib Alpaca Shawl

-

08/16/2023NEAFP Article: Email Marketing is still a MUST do for all Alpaca Farms

-

06/27/2023NEAFP Article: Off the Beaten Path Agritourism Ideas

-

04/06/2023Take our 2023 NEAFP Fiber Collection Survey!

Alpaca Coloring Pages

- Happy Memorial Day 2024: Alpaca's Grazing

- Winter #1: Build a Snowman Activity

- Winter #2: Extreme Sports

- Valentine's Day: Alpaca Wedding

- St. Patrick's Day: Leprechaun

- Spring: April Showers

- Summer: Beach Day

- 4th of July: Colonial Alpacas

- Summer: Farmer's Market

- Fall: Apple Picking

- Halloween #1: Costume Contest

- Halloween #2: Spooktacular Halloween

- Thanksgiving #1: Giving Thanks Activity

- Thanksgiving #2: Pilgrim Alpacas

- Christmas #1: Deck the Halls

- Christmas #2: Santa's Workshop

Alpaca Fact Series

Business Resources

- Article: Email is still a MUST DO for all Alpaca Farms

- Article: Off the Beaten Path Event Ideas on the Alpaca Farm

- Download: Sock Photo Download Folder

- Graphics: Shop Small this Holiday Season

- Article: Form Follows Function: Dressing for Fall and Winter 2020

- Graphics: Sock and Handwear Comparisons

- Article: A Change in the Seasons: Farms Continue to Adapt into the Busy Harvest Season

- Graphics: How to Support Alpaca Farms

- Graphics: Alpaca Fiber Properties

- Article: Customer Retention: Building Customer Loyalty for your Ecommerce Business

- Article: Harnessing Storytelling to Market Your Business

- Article: The New Normal and a Renewed Support for U.S. Alpaca

- Article: Use Gift Cards to Increase Sales

- Article: Virtual Farm Tours: Bringing People & Alpacas Together in the Virtual World

- Graphics: Get the Most out of your Fiber Harvest

- Graphics: Alpaca Knitter's Yarn Guide

- Article: Mike and Sean's Adventure in Retailing

- Article: Harnessing Holiday Sales Momentum into the New Year

- Graphics: U.S. Alpaca Holiday Gift Guide

- Graphics: Small Business Saturday Resources

- Article: Tools and Topics for Implementing Healthy Soil Agriculture

- Article: Successful Social Media Marketing for Alpaca Farms

- Article: Agritourism on the Alpaca Farm

- Article: Finding Success at Fall and Winter Markets

- Article: Brand Identity & Your Local Community

- Article: Social Media: Alpacas are STILL Seriously Trending

- Article: Let's Get Personal: Expanding your Inventory with Product Personalization

- Article: Part 2: Promoting your Brand Online through Product Styling

- Article: Promoting your Brand Online through Product Styling

- Article: 7 Old School Ways to Spread the Word about your Event

- Article: 5 Ways your Open House can increase Future Sales

- Article: Top Alpaca Related Hashtags to increase your Reach!

- Article: Alpacas are SERIOUSLY Trending

- Article: How to Utilize CO-MARKETING

- Article: Farmers Share their Booths and Tips

- Article: Mobile Payment Survey Results

- Article: Product Photography Do’s and Don'ts

- Article: Driving Business After the Holidays

- Article: Marketing Reflection and Planning

- Article: The Slow Alpaca meets Slow Fashion

- Article: Use Gift Cards to Increase Sales

- Article: The Importance of Being Mobile Friendly

Article: The Slow Alpaca

The Slow Alpaca

by Sean Riley

Originally published in the 2016 Showtacular Showbook

Over the last 30 years there’s been a noticeable shift in consumer mentality around the globe, particularly in regards to our modern day food systems. Through the democratization of knowledge, populations across the planet have gained access to more information and have become better informed about the food and products they consume daily. In 1986, when a McDonald's franchise was being constructed in Rome, Italy, an Italian Journalist Carlo Petrini became outraged and the Slow Food movement was officially born.

Petrini saw the uprising of the industrial, multinational corporatization of the global food system a direct threat to Italy's rich culinary history and ultimately the rest of the world's national and regional food systems.

“We are enslaved by speed and have all succumbed to the same insidious virus: Fast Life, which disrupts our habits, pervades the privacy of our homes and forces us to eat Fast Foods... A Firm defense of quiet material pleasure is the only way to oppose the universal folly of Fast Life... May suitable doses of guaranteed sensual pleasure and slow, long-lasting enjoyment preserve us from the contagion of the multitude who mistake frenzy for efficiency. Our defense should begin at the table with Slow Food. Let us rediscover the flavors and savors of regional cooking and banishing the degrading effects of Fast Food.” (Excerpt from the Official Slow Food Manifesto, as published in “Slow Food: A Case for Taste” in 2001).

The Slow Food movement at its core strives to counterbalance the growth of global, industrial, centralized food systems that destabilize regional economies while prioritizing profit margins over all else. With profit and growth the underlying motivation behind all decisions, it becomes inevitable that the quality and nutritional value of the food and food products produced will deplete over time while off balance sheet resources are exploited. What we end up with is a food system that’s disconnected with its natural origins and no longer serves the people it’s feeding or the land it’s grown on. Fast, industrialized food in it’s current form, is simply not sustainable. Out of necessity, comes invention, and the Slow Food movement was born.

One major sign of the Slow Food Movement that we’ve all experienced in the last decade is the rise of Farmer’s Markets. Over the last 20 years Farmers Markets have grown by almost 500% in the U.S. These markets have sprung up as community places where local and regional farms can bring their products direct to consumer. According to the American Farm Bureau Federation, a farm selling produce through a typical grocery chain store distribution model will only make upwards of 19% profit on the food they produce. By taking their produce direct to the retail market, the farm is able to see a much higher profit margin, allowing them to be more sustainable on smaller scale operations. Across the country, many alpaca farms take part in this grassroots community movement by sharing their alpacas, the fiber, and the products it produces with their local communities. The slow and steady rise of the Slow Food Movement and the localized community food markets that have sprung up to support it are the result of people asking new questions about the food they consume:

What is the food that I eat made from?

Where and Who grows it?

How is it grown and made?

Is it grown in a healthy and sustainable manner?

Who benefits from its sale and consumption?

With the growth of the Slow Food movement across the globe over the last 30 years, it’s apparently clear the impact the general consumers shift in purchasing has had on the larger food industry. Local, Regional based food economies have grown exponentially, along with the rise of organic, non-GMO, and farm to table business and marketing initiatives. It is safe to say that the Slow Food movement has officially become an industry in its own right, as well as begun influencing industries outside of food itself.

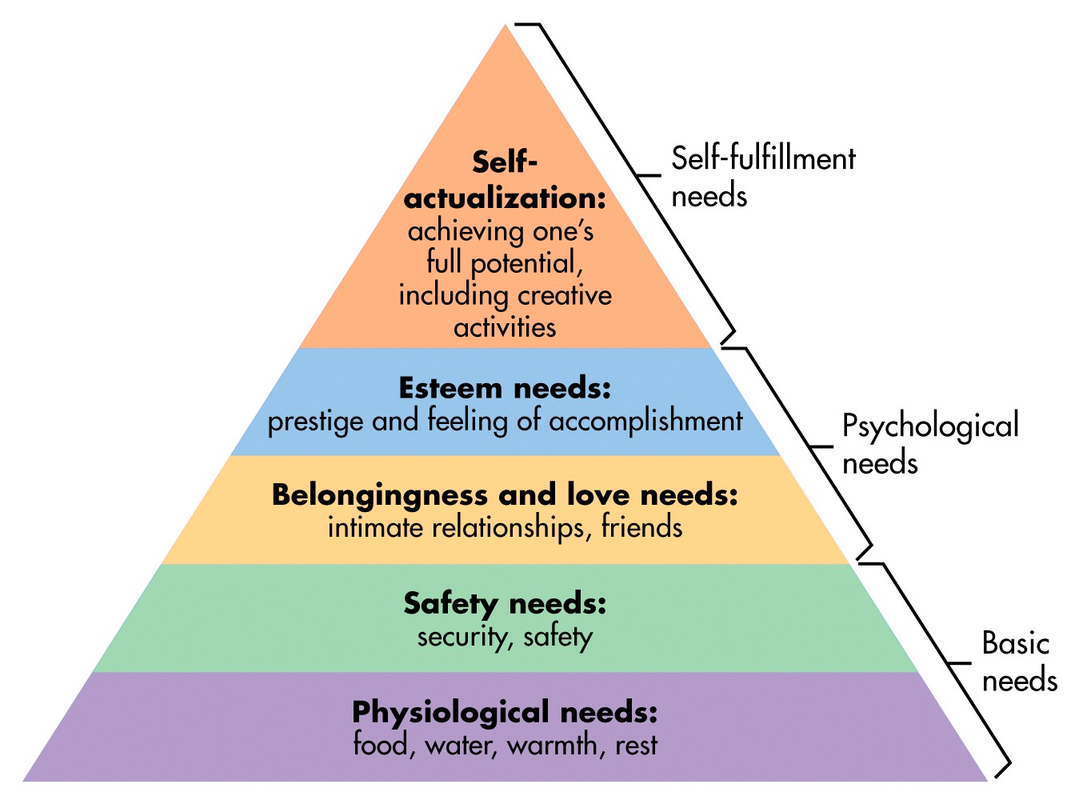

Food, being one of the, if not the most essential need for human survival, was the first of many global industries to be disrupted through this shift in consumer perspective. Another pillar on the base of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs Pyramid is Clothing; the next logical step for this growing frontier.

The Slow Fashion term was officially coined by Kate Fletcher in 2007, at the Centre of Sustainable Fashion in the UK. Slow Fashion is not a seasonal trend that comes and goes like animal print, but a sustainable fashion movement that defines itself as: a term which describes clothing which lasts a long time and is often made from locally-sourced or fair-trade material, ultimately contributing to a more sustainable society and economy. The Slow Fashion movement, like the Slow Food Movement, is a direct response to the off the accounting book costs to the Fast Fashion world we find ourselves in today where clothes are made to be worn once, fall apart after a few wears, and be thrown away and replaced soon after. It's time we started to embrace the Sustainable Fashion Movement.

With the rise of Fast Fashion over the last 20 years, where trends are measured in days instead of seasons and the life span of a garment is measured in months instead of years, the Fashion industry has proven to be ripe for disruption via the Slow ideals movement. Like the Slow Food movement that grew organically as a direct response to Fast Food threatening a rich culinary history, Slow Fashion is positioning itself as a counterbalance to the recent wear once retail trends of the late 90s and 2000s. Much like Fast Food, Fast Fashion lacks connectedness, soul, & integrity. Cheap, mass produced garments are generic and expendable and don’t hold any true value besides making the purchaser feel trendy for that small window of time the garment is indeed considered “fashionable.”

In order to drive sales, Fast Fashion brands offer their garments at the lowest possible cost to consumers and maintain profitability by producing goods as cheaply as possible. To reduce the cost of the products they produce and maintain profitability, they’ve turned to moving the true cost of these products off their accounting balance sheets. These true, “unaccountable” costs of the Fast Fashion industry are the exploited labor force in developing nations, the rampart pollution in countries with lax environmental protection laws, the wasteful use of energy to move material and goods across the globe, and the loss of self sustainability of national and regional economies. Besides the true costs of Fast Fashion piling up on the manufacturers end, we are also starting to see the indirect result on the consumer side.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics and the EPA Office of Solid Waste, the average American Family spends over $1700 on clothes a year while each member of the household throws away 65 lbs of clothing during that same period. In 1930, the average American Woman owned 9 complete outfits, today it’s 30(Forbes). Although the average American’s wardrobe and need for closet space is expanding, the majority of us still wear only 20% of our clothing 80% of the time.

The alternative to all of this is the slowly growing alternative of ethically sourced and produced Slow Fashion. The garments are made from low impact, renewable resources and designed to be durable and last. Produced in an ethical environment, free of exploitative labor, hidden pollution and environmental costs through global transport and finishing/dyeing techniques, and the reduction of hazardous chemicals in the manufacturing process. The movement calls for accountability through the entire production life cycle of a product, from the time it’s raw material, all the way through it’s manufacturer, purchase, & use.

Much like the Slow Food movement, as more people become aware of the true, off balance sheet costs of the clothing they purchase and wear everyday, people are looking to educate themselves and seek out alternatives and the Slow Fashion movement is a direct result in this shift in consumer behavior.

In order to truly understand the impact of any particular product, we have to analyze its Life Cycle. We can follow it from Raw Material, Processing, Assembly, and Distribution to the end user to better understand its true impact and story.

Although the U.S. accounts for 28% of the world's clothing purchases, only about 2% of those garments are made in U.S. based textile mills. When analyzing a typical Fast Fashion cotton t-shirts product life cycle, from raw material in the field to finished product ready to wear, we can start to appreciate the true environmental and social costs behind the limited time $4.99 price tag. The typical cotton t shirt starts off as cotton in the field, consuming tremendous amounts of water, petroleum based pesticides, herbicides, and fertilizers to grow and flourish. Once harvested, it begins consuming vast amounts of energy to be transported across the globe and turned into yarn and fabric. The cotton fabric will be dyed using hazardous chemicals that if not handled properly will pollute the local environment. From there it will travel across the globe again, to be cut, sewn, and finished, in most cases by exploited labor in developing nations with little to no labor protections in place. Now that it’s a finished t-shirt, it will travel even further to eventually reach a retail rack near you; to be purchased, worn, lost in the back of the closet, and eventually forgotten.

As we learn about the true costs behind fast fashion, it’s natural that alternatives begin to pop up on the other end of the spectrum. The U.S. Alpaca Fiber Industry is a great example of one such counter balance point. When following the flow of a U.S. Alpaca Products life cycle, we can see the stark differences.

The Alpaca fiber starts off in the field, being grown on an animal that is an efficient eater, consumer of water, requires little intervention, and with it’s padded feet physically treads lightly on the land. Once humanely harvested, the fiber is collected before being sent off to domestic textile mills & turned into yarn and fabric. The U.S. based textile mills are in many cases century old businesses, with strong labor and environmental protections put in place to ensure the quality of their work environments and to safeguard their local communities from unwanted pollution. From here the finished yarn and fabric goes off to to be knit, woven, cut, sewn, and finished by a U.S. skilled craftsman earning a living wage. In the case of the current U.S. Alpaca Fiber Industry, a vast majority of those finished products end up back on the farm to be brought directly to local market. When the same alpaca farmer who raised the animal, and harvested the fiber is also sharing those finished goods with their local communities, they receive the highest profit margin on the fiber.

This is a simple analysis of the production life cycle when comparing the status quo fast fashion cotton t-shirt, to the ever Slow U.S. Alpaca good, but it’s very clear to see the stark contrast. Due to the size of the U.S. Alpaca industry and being a high cost producer of fiber, U.S. alpaca farms will not be able to compete on the global commodity market. Although we can’t compete on price and volume of raw alpaca fiber in international markets, we are positioned to take our goods directly to one of the largest textile market places in the world which happens to be located right in our backyards. We don’t need to compete with the existing Fast Fashion paradigm, but rather define our own game where we already have a strategic advantage.

Ana getting ready to sew at NEAFP.

As farmers, fiber growers, and in many cases the retail distributor, it’s important that we acknowledge this growing shift towards Slow Fashion, it’s ideals, and how we can position ourselves as individual businesses and an industry to cater to it. The Fast Fashion system we have in place today is simply not sustainable and it's true underlying costs are beginning to pile up around the planet and can no longer be ignored. As more people wake up to the truth behind the garments they purchase everyday, the demand for more sustainable and transparent options will rise.

Carol inspecting Survival Socks before labeling at NEAFP.

It boils down to sharing our story, about the alpacas, their fiber, and the finished goods they produce. Along with the normal selling attributes like warmth, strength, and comfort factor, we need to also be sharing it’s back story. The majority of U.S. Alpaca products that are being produced in the U.S. have a positive, low impact supply chain behind them that directly benefits many local and regional economies around the country. We need to study Slow Food and the problems that it is solving, and contemplate the questions that people are beginning to ask about their clothes.

Matt preparing orders for shipment at NEAFP.

We already have the answers that our future customers are asking:

What is it made from? Where & How is it made? Who benefits from its sale?

Each purchase of a product Made in the U.S. from U.S. Grown Alpaca Fiber, supports the farm or small business that brought it to market, the farm & alpacas that produced the fiber, and the many textile mills that helped manufacturer it. As people become conscious of where, how, and of what their clothing & accessories are made from, the U.S. Alpaca fiber industry will be there to service and grow with this expanding market.

With the democratization of knowledge, through the growth of the internet age, it’s never been easier to connect to our peers and share our story. We have the tools to send information across the planet and back in a split second, it’s time we crafted our message and positioned ourselves and our alpacas as the poster children of the rising Slow Fashion movement. While showcasing our animals, the great attributes of their fiber and clothing made from it, we need to humanize the people and the mills behind their production. At every step along the way, from raw fiber in the field to finished goods at the farmer’s market, U.S. Alpaca products feel warm and fuzzy at each step of the way, it’s time we showcase and share that love with everyone.

Written by Sean Riley of the New England Alpaca Fiber Pool Inc. - August 2016